How it started

In more than the century-old-history of Bollywood, the femme fatale has assumed a variety of rules – the widowed mother, the pretty damsel in distress, the one waiting for her true love or, (rarely) the woman who takes charge of her own fate. Interestingly (and ironically), the 50s and 60s saw some rare flashes of brilliance, when it came to women centric characters, with Nargis Dutt’s Mother India leading the roost (1957); the gut wrenching story of a mother, who kills her own son, when he turns rogue and brings shame to the village. Guide (1965), was another example, as the feisty Rosie, caught up in an unhappy marriage, decides to follow her passion, with a man she loves. Revolutionary, for those times.

However, these roles were spread far and wide, and the next few decades saw female actresses being relegated to the roles of a devoted mother, wife or girlfriends. Some movies like Sadma (helmed by a brilliant Sridevi in 1983) managed to scrape the surface once in while, but found little to no support in the decades following it.

The stereotypical woman

Dr Shoma A. Chatterji, Indian film scholar and author throws some light on it and says, “Till the 1990s, Bollywood mainstream kept focussing on the beauty of the face of the leading lady and stressed on her romance with the hero which could also mean her wilful inclusion into the extended Indian joint family as one witnessed in Hum Aapke Hain Kaun or perhaps in Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge where love was the primary emotion either seconded or equalled with conventional family values. Beauty of face and figure, lots of song-dance sequences formed the major slice of the women. Dil To Pagal Hai is another example.” In all these movies, the core focus of a woman was to find a man, fall in love and settle down, all while dreaming of a Prince Charming arriving on a white horse, literally speaking! The wave of Yash Chopra universe, replete with chiffon sarees, snow capped mountains, and love ballads, as pleasing to the eye, did little to nothing to better the portrayal of women in cinema. Even author backed roles like Chandni (1989), focused solely on a woman’s journey to find love, brushing all her other accomplishments aside. One of the few exceptions was Lamhe (1991- incidentally from the Chopra camp) where a younger woman is shown to be brazenly falling in love with an older man, who incidentally, was in love with her mother, who was older than him. Largely ahead of its time, the movie did lukewarm business due to the inability of the audience to digest a topic like this.

When did change start rolling in?

The scenario changed steadily and very powerfully with the advent of the 21st century. Talking about it, Dr Shoma A. Chatterji said, “Kahaani 2 (2016) and Mom (2017) are two new films that turn the screen mother on its head by offering insights into two mothers whose daughters are not their biological offspring but they are no less caring or stressed by the fact that they are not the biological mother. The sparkling performances of Vidya Balan and Sridevi respectively, bring out how well two powerful actors across two generations can realise the challenge of turning the tables on the screen mother for good”. New age filmmakers like Zoya Akhtar, Meghna Gulzar, and Gauri Shinde joined in the party, to produce women centric gems like Dil Dhadakne Do (2015), Raazi (2018), and English Vinglish (2012)

Embracing their true selves

In Shoojit Sircar’s Piku (2015), Baskhor Banerjee, portrayed by Amitabh Bachchan, who lives with his single daughter Piku (Deepika Padukone) tells a potential suitor at a party that she is not a virgin. Piku, slightly embarrassed, moves aside in a huff, but the otherwise eccentric and paranoid Baskhor firmly believes that Piku should get married for the right reasons, and not to be someone’s ‘wife’. While there might be a tinge of selfishness in that attitude as a ploy to keep Piku all for himself, his reasons were not without logic. Finding a man and getting married should not be the sole duty of a woman, both on and off-screen. Cut to Anurag Kashyap’s Thappad (2020), where a simple, middle class Amrita (Taapsee Pannu) gets married into the well-to-do Sabharwals, and is happily pursuing the role of a housewife (happily being the buzzword here), until a drunken brawl at a party sees her husband slap her in front of a sea of people. Part shocked, part numb, Amrita is jolted to realize that she had been living in her husband’s shadow all along, and in the process, lost a part of herself, even not remembering that her favorite color is yellow and not blue (as liked by the husband).

Do we still judge our female leads?

Even though more characters are being written for women, they are unable to escape the prying eyes of the audience, and are constantly judged. This issue unfortunately, transcends generations and still riddles Bollywood, which equates vices like smoking, drinking and being open about their sexuality to a ‘loose’ moral ground. Case in point is Veronica from Cocktail, portrayed by Deepika Padukone (2012). The affable Veronica befriends a docile Meera (Diana Penty) and they both end up falling in love with the same man, Gautam (Saif Ali Khan). Inspite of having a casual relationship with Veronica all along, Gautam ends up falling in love with the miss ‘sanskari’ Meera, who, his boisterous Punjabi mother loves, unlike Veronica, who wears skimpy clothes, and is hence, not ‘qualified’ as wife material. Similarly in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998), Rahul ignores his platonic tomboy best friend Anjali and falls head over heels in love with college heart-throb Tina. Years later, Tina dies and Rahul reconnects with Anjali, only to fall in love with her post a (feminine) makeover!

Why demonise ‘strong’ characters?

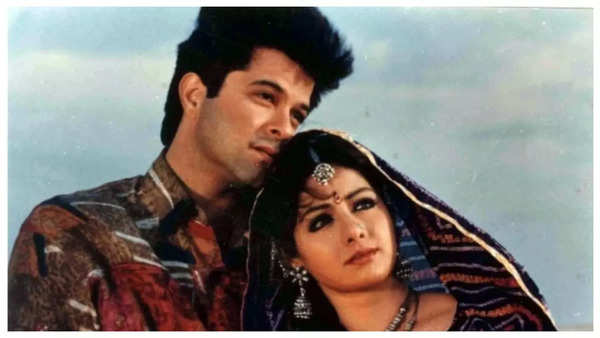

Writer Siddharth from Siddharth-Garima, who wrote movies like Ram Leela, Toilet: Ek Prem Katha etc, tells us, “We have always judged strong women characters because it is a patriarchal society, and any change is often open to judgement.” In Bollywood specifically, if a woman is shown strong, she is either a negative or ‘grey’ character. In Laadla (1994), the headstrong businesswoman Sheetal (Sridevi) is juxtaposed against the coy and homely Kajal (Raveena Tandon). While she marries Raju (Anil Kapoor) out of sheer spite, she eventually realises her ‘mistakes’, and in the end, gives up her job, dons a saree, and prepares a ‘dabba’ for Raju to be qualified as the ‘perfect’ wife! Of course, not all is dark and gloomy. The path-breaking Astitva (2000), directed by Mahesh Manjrekar is the story of a woman Aditi, (Tabu) who finds love outside wedlock, when trapped in an unhappy marriage. Not only is the protagonist shown as unapologetic, she also proudly choses to walk out, when both her husband and son morally shame her for having a relationship outside marriage.

Welcome change now?

The brutally honest late Rishi Kapoor, once during an interview in 2009 told me, “Hum, at the end of the day, sirf love stories hi banate hai.” While it is unfortunate that he is not around anymore, what he said held a lot of water, at least back then. Now, self love remains the cornerstones of all female characters (or most of them), and they are not necessarily driven by the love for a man. In Queen (2013), while Kangana’s character Rani starts off as a shy, docile west delhi punjabi girl, who is desperate to be accepted back by the fiance who jilted her, she slowly mushrooms into a strong, almost new person, on a solo trip to Europe, who needs no man for validation. On the contrary, she gives her now x fiance a little hug at the end, thanking him, signaling that had he not ‘dumped’ her, she would not have ever found herself. Similarly, in English Vinglish, the simple Maharashtrian housewife Shashi (Sridevi) knows that her otherwise lovable husband is ashamed of her since she can’t talk in English. Initially looking for validation, Shashi turns into her own person when she learns English, and realises that the only validation she needed was from her own self.

Driving a change

Talking about how movies can drive a change in the society, Garima (Siddharth-Garima) said, “After Toilet: Ek Prem Katha (2017) released, a panchayat in Haryana made a rule that a bride has the right to walk out of her husband’s house, if there is no toilet.” When asked whether times have changed, Garima said that nowadays more stories are being written about women, and that is a welcome change. She added, “When we were writing Leela, we knew she had to be feisty, unapologetic and strong, so much so, that she could hold her own against Ram (Ranveer Singh) and in no way, was less than him, if not more.” On a parting note, Siddharth leaves us with hope, “Things have now changed, as the definition of a strong woman too, has changed for the better.”